IDENTIFYING how old fish are is fundamental to knowing how fast they grow, how old they are when they reproduce, and how long they live.

The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries uses this data to estimate the number of fish in different age groups and how this changes over time.

These details help the department assess the sustainability of fish stocks:

OTOLITHS ARE EAR BONES

Otoliths (ear bones) help fish orientate themselves and maintain balance, acting like our middle ear.

They are composed of a form of calcium carbonate and protein, which is deposited at different rates throughout a fish’s life.

This process leaves bands (alternating opaque and translucent bands) like the growth rings in a tree.

The otoliths are located within the skull behind the eye and directly below the brain. Otoliths come in different sizes and shapes depending on the species of fish. They can be slender and fragile (e.g. mackerel and cobia), large and chunky (e.g. barramundi and snapper) or symmetrical in shape (e.g. sand whiting).

HOW EAR BONES ARE USED TO ESTIMATE AGE

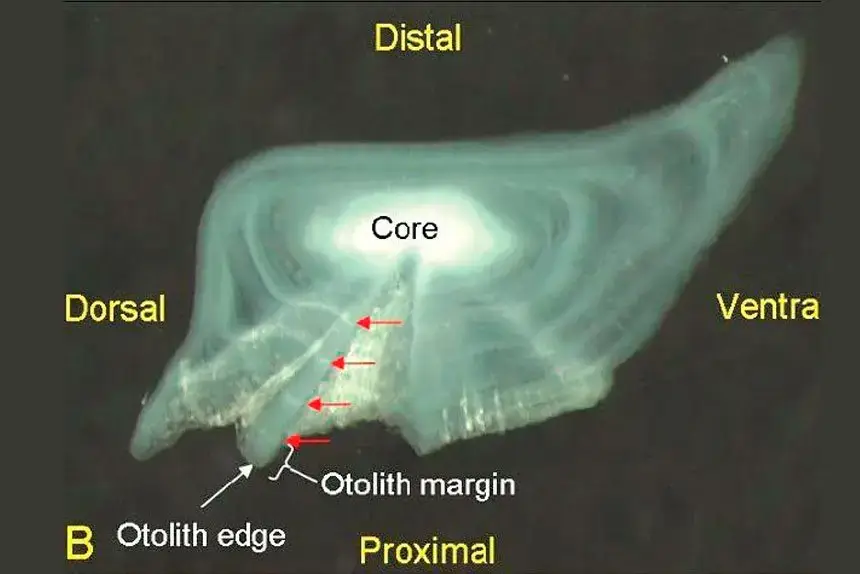

To estimate fish age, fisheries scientists examine the otoliths and count the number of opaque bands – like growth rings in a tree.

This information, plus the date the fish was caught, the birth date (middle of the species’ spawning period) and the period that opaque bands were deposited, are used to estimate the age of the fish.

COUNTING OPAQUE BANDS

Otoliths are interpreted by counting the number of opaque bands between the core and the edge, and measuring the otolith margin (the distance between the last opaque band and the otolith edge).

The width of the otolith margin tells us when the last opaque band was deposited.

USING WHOLE OR SECTIONED EAR BONES

Otoliths can be interpreted whole or they may need to be sectioned by cutting a thin slice from the otolith through the core.

Sectioning otoliths enables a clearer view of the banding patterns in some species.