A BRIEF but pivotal era in motorsports history gave birth to some of the most exhilarating and legendary automobiles ever created.

This period, characterised by unrestricted displacement and groundbreaking innovations, propelled motorcars to an unparalleled level of performance that remained unchallenged for decades.

No other epoch in motorsports history featured such massive power plants at the pinnacle of competition.

This peak, which lasted from 1904 to 1908, was exclusively reserved for racing and never intended for public road use, and the few surviving examples of these cars have become highly sought-after artifacts in the annals of motoring history.

During this era, Mercedes dominated the technical landscape, occupying a virtually unchallenged position of superiority.

The Mercedes, which was introduced in 1901 by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft, quickly established its reputation as the finest car of its time. The masterwork of Wilhelm Maybach and Paul Daimler’s design team, the Mercedes built upon earlier designs of Gottlieb Daimler, Paul Daimler, and Panhard et Levassor.

The Daimler motorcars that existed before 1902 were still heavily based on Gottlieb Daimler’s pioneering designs of the 1880s.

With intake valves of the atmospheric type, opened by suction, and engines regulated by a governor keeping them at a constant 800rpm, the operator had little control over the engine besides selecting gears.

Ignition was either by hot tube or mechanical make-and-brake, again with no control by the operator, while chassis were quite high with unusual transaxles and chain drive.

These Cannstatt Daimler cars were high-quality and expensive machines, but by 1901 were heavily outclassed by the products of France.

Enter Emil Jellinek, a DMG sales agent and motoring enthusiast. He felt Daimler was not producing cars as modern as the competition and challenged engineers to design something

“Not for tomorrow but for the day after tomorrow.”

To tempt Maybach engineers to design this superior car for him, he offered a prize of 550,000 DM.

Maybach delivered on the challenge, producing the groundbreaking product we now know as a Mercedes.

To avoid conflicts with licensing of the Daimler name throughout Europe, DMG needed a different name for this product, so Jellinek’s daughter Mercedes became the namesake.

Wilhelm Maybach’s innovations included large, mechanically operated intake valves, a refined spray-jet carburettor with throttle and automatic mixture control, and a flexible, driver-controlled engine, replacing the mechanical governor.

The Mercedes/Bosch make-and-brake ignition system provided full control over ignition timing, while engine displacement was significantly increased, with more aggressive camshaft timing resulting in a responsive and powerful motor far surpassing anything Gottlieb had envisioned.

The Mercedes was promptly fitted into a chassis heavily influenced by the Panhard et Levassor and Paul Daimler’s light car design but now featuring longer and lower pressed C-channel steel frame members. A remarkable transaxle with four-forward speeds and a groundbreaking H-pattern shift quadrant completed the package. These innovations produced the first truly modern high-performance automobile.

The 35hp version, initially the highest performer, was followed by the legendary 60hp. Despite its introduction in 1902, few cars could match its stellar performance, even a decade later.

Daimler knew racing success sold cars so he was determined to dominate the highest level of competition, and the new Mercedes racing cars quickly showed their capability against their established rivals.

The 60hp race cars claimed prominent victories in the Coupe Gordon Bennett and the Vanderbilt Cup in America.

However, a devastating fire soon destroyed the factory fleet of rennwagens. In a daring move, Daimler borrowed previously sold customer 60hp cars to compete in the upcoming grands prix.

Despite the success of the 60hp, Daimler faced significant challenges in creating a superior successor. The much-anticipated 90hp model failed to meet expectations, while a short-lived six-cylinder racing model, despite its impressive 120hp, also proved to be a flop.

Recognising the importance of returning to the foundation that had made the 60hp such a landmark, Mercedes decided to revert to its roots.

In 1907, Mercedes showcased its technical expertise once more by assembling a comprehensive racing package that dominated the competition. The focus was on optimising their core technology and crafting a meticulously designed complex package.

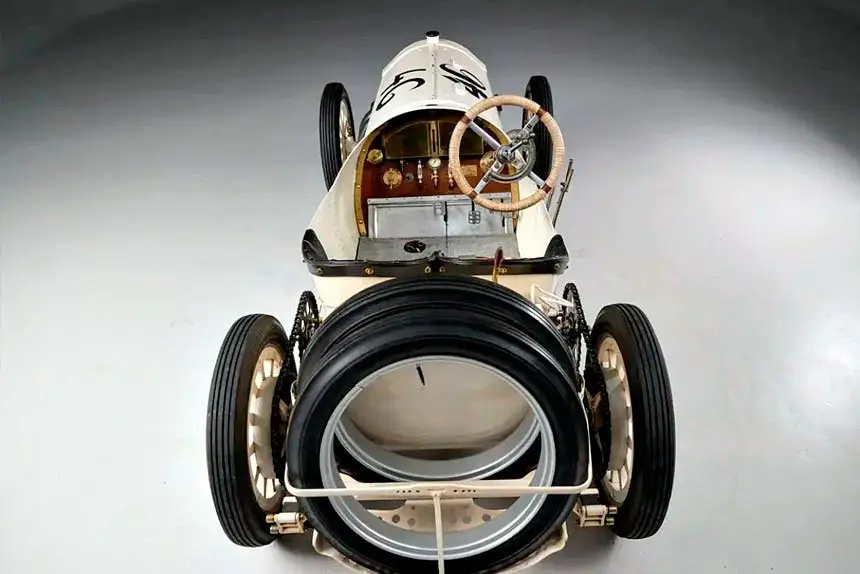

The most striking innovation was the fully enveloping coachwork that provided protection for both driver and mechanic.

This exceptional bodywork stands as a high point in the racing car aesthetics of its era.

All these innovations resulted in a car that stood out starkly from its contemporaries, sitting low to the ground and appearing significantly lighter than its rivals.

The new Mercedes racing cars would be termed “Brookland” type and would prove a return to form for DMG. A decisive victory by Lautenschlager at the 1908 French Grand Prix showed German prowess in a country that had dominated the automobile industry for years.

For 1908, a specially enlarged version of the 120hp engine was constructed. Rated at 150hp, this engine represented the most powerful and largest Mercedes engine ever built, as well as the most potent iteration of the original Mercedes engine design.

The new Semmering Mercedes, equipped with front fenders and road equipment, was designed to be driven directly from the German factory to Austria for the hill climb.

Mercedes team GP driver Otto Salzer personally piloted the car to the event, ultimately securing a decisive victory, surpassing his teammate in second place.

For the 1909 event, Mercedes developed a unique and hardier engine of the same displacement; it’s remarkable to think of a manufacturer in that era constructing a one-off engine for a single event.

Mercedes’ efforts were once again rewarded as the new engine, coupled with further lightened chassis configuration, propelled Salzer to victory once again.

The Semmering Mercedes would race one more time for the factory, this time driven by the “Red Devil” Camille Jenatzy in the unlimited displacement race in Belgium.

From there, Daimler sent the car to London, where it was purchased by wealthy Australian sportsman Lebbeus Hordern.

It passed through the hands of a few other Australians and notably made an appearance at an event marking the introduction of the new Mercedes 300.